“If you’re gonna spew, spew into this.”

I was thinking of the cult-classic scene from the movie Wayne’s World during the Mountain Lakes 100-mile ultra.

“You really need to eat,” my ride-or-die crew Shazam Smith told me. “Eat this...Now!”

She handed me an oversized Huma Recovery packet and tried to convince me to slurp it down.

But I couldn’t do it. By mile 57 around 11 p.m, the suffering was already real.

I was freezing in wet clothes for hours by the time I reached Olallie Meadows in Oregon’s Mount Hood National Forest. I wasn’t eating or drinking. I was close to vomiting. And I started thinking this might be the end.

Stuff happens. Things don’t always go as planned. You forget some essential gear. You take a fall. You get lost. Maybe self-doubt gets the best of you. Whatever. There’s always the possibility of a DNF, even for the most well-trained and experienced runners.

What should you do when you feel like you can’t go on?

Sometimes a DNF is the only option, and the smart option. But experience is a great teacher. After running 100-mile races (9 finishes, 4 DNFs), I’ve learned a few things about what it takes to go the distance.

But after months of training, looming cutoff times, and an imminent DNF at the Mountain Lakes 100 hosted by Go Beyond Racing, I wasn’t ready to give up.

Maybe it was time for the Vomit Method. Here’s what happened...

How do you train to run 100 miles?

There’s actually more than one way to do it.

After some major suffering during the Cascade Crest 100 in Washington during my first 100-mile ultra about a decade ago, I dropped out at 88 miles.

And I vowed to become a better ultrarunner.

Beginning in January…

Run 3-4 days a week. The big runs in 2021 included:

Lift weights 3 days a week: The primary exercises included:

Would it be enough to go the distance and finish the Mountain Lakes 100?

The Perfect Storm for Failure

In the final weeks and days leading up to the Mountain Lakes 100, the perfect storm for failure started to develop.

Tight glute and hamstring: Out of nowhere, I developed a tight left glute and hamstring. I’ve been running injury-free for almost 25 years. Aggressive foam rolling and stretching seemed to help. But would this ultimately take me out of the race early?

Getting sick: A couple weeks before the race, I got sick. Cold-and-flu sick with a sore throat, coughing, congestion. I’m double vaccinated. Took a COVID test anyway that came back negative. Forced to start tapering earlier than I wanted to.

Mother Nature madness. It’s been an unusually dry summer in the Pacific Northwest. Lots of days over 90 degrees. Lots of sun. And barely any rain. It was even a perfectly sunny 70-degree day during the Mountain Lakes 100 packet pick up.

But on Saturday, the forecast was completely different. Rain, wind, cold temps. Another factor to make running 100 miles even harder.

MILE 0: It’s Raining...It’s Pouring...

8 a.m.: It’s go time! Go Beyond Race directors Todd and Renee Janssen give 140 runners last-minute instructions and advice at the Historic Clackamas River Ranger Station.

“Do your best to stay dry, but realize you’re gonna get wet,” Todd says. “At some point, you’re gonna feel like quitting. There’s going to be some high and lows. If you’re thinking about dropping, give yourself some time before you do.”

“10...9...8...7...6...5...4...3...2...1…”

With the clanking of cowbells and a cheering crowd, I find my place at the back of the pack.

MILE 31: It’s Just a 50K

11 a.m. I make my way around Timothy Lake, stopping at the Little Crater Lake Aid Station for some candy bars, peanut-butter pretzels, and potato chips. Then climb about 1,400 feet to Frog Lake, sipping on a Skratch Labs potion and eating a mix of food and Huma Gel.

2 p.m. I make the return trip to the Timothy Lake Dam and ranger station, leapfrogging with other runners, chatting about training, epic races and work. Sometimes just running in silence.

When I arrive around 31 miles, my ride-or-die is there waiting with a warm truck, dry shoes and clothes, food and drinks to restock my pack.

“You’re doing great,” she says. But inside, I’m not so sure.

I find out the rain and cold has already taken out some experienced runners. And my glute and hamstring was questionable.

MILE 57: Time to Climb

10:30 p.m. It takes me a lot longer to make the climb from the ranger station to Olallie Meadows and cover 26 miles in wind, rain, mud and darkness.

My wool mittens get soaked early on, so I stuff them in a pocket hoping my hands can survive.

But they don’t really. My fingers get so cold, I stop drinking and eating because messing with the bite valve on the hydration pack or tugging at zippers is too hard.

There’s more leap frogging. The remote aid stations offer a little respite from the conditions with a warming tent, hot broth, bacon, and quesadillas.

A runner in a parka ahead of me takes a fall and gets soaked in mud and rain. When he gets up, he’s already made up his mind to drop at Olallie Meadows.

I’m so cold and wet, I wonder if I’m next. But I keep moving.

A volunteer at the Warm Springs Aid Station gives me some hand warmers.

When I finally make it to Olallie Meadows, I’m feeling the heaviness of dropping out.

I’m tired. I’m freezing cold. I haven’t been eating or drinking well. And I’m even a little mad. I train all year to run the Mountain Lakes 100 (it’s the 7th year I’ve stepped up to the starting line).

And the last thing I want is a DNF.

My ride-or-die is there. Lots of cowbell + the loudest voice in the crowd.

“Yeah, Evan….You got this!” It’s easy to spot her in the crowd of runners and volunteers...blonde, 6 feet tall, lots of moxie.

She’s my lifeline in this race. My only crew. And fittingly, the very person who pulled me out of a deep dark hole a couple of years ago when I thought all hope was lost.

“Come on, let’s change your clothes and get you warmed up,” she says.

Every piece of clothing is soaked. And with temps hovering around 40 degrees, I’m freezing.

I huddle under a blanket inside a truck with hot air blowing on me. It takes about 1.5 hours to get warm and change clothes, and my stomach still isn’t right.

“You really need to eat,” my ride-or-die says. “Eat this...Now!”

I refuse. I tell her I can’t. But she persists. After crewing for several 100s and 50-milers, she’s learned how to help me keep going.

She hands me an oversized Huma Recovery packet and tries to convince me to slurp it down.

“No,” I tell her in a pathetic man-child voice. “I’ll just vomit red splatter all over the place.”

“Remember when you asked me to crew you?” she says. “I’m here to help you finish. Eat this...Now!”

I gulp down a huge mouthful of Mixed Berry Recovery Gel.

And then it happens…

I fling open the truck door and lean out into the darkness. Coughing, sputtering, dry-heaving, and vomiting.

And strangely, it’s just the thing I needed to recharge.

12 a.m. I finally leave Olallie Meadows and learn the cold and wet conditions have taken out more runners. And 40 miles still seems like a long way to go. Can I make it?

The return trip takes me past Pinheads, Warm Springs, and Red Wolf Aid stations.

The rain takes a break, but it’s still cold.

I stay too long in a warming tent at one of the aid stations. And get a speech from Grandma "Liz" Red Wolf about the cutoff times. She taped up my foot a couple years ago at the same stop, saving me from a painful blister. And I saw her at Cascade Crest 100 a couple years earlier.

I swig a 5 Hour Energy shot when I really start to feel the drain of sleep deprivation.

And the dad-joke aid station perks me up. Maybe finishing is still within reach.

MILE 85: ‘I Can’t Run’

8 a.m. During the night something unexpected happens. My tight glute and hamstring miraculously disappear during the downward descent back to the ranger station.

Instead, my left hip flexor decides it’s done with climbing over roots and rocks, dodging ankle-deep puddles, and shifting in mud. And it’s done with running, too.

“I can’t run,” I tell my my ride-or-die quietly when I reach the ranger station. But with 6 hours before the 30-hour cutoff, I’m confident I can walk my way to the finish.

It’s a mind game now. Wave the white flag and surrender or put one foot in front of the other and go.

I’m not quitting. Not now. Not yet. Not while there’s still time.

Sometimes a DNF is inevitable, I’ve been there before and felt the sting of defeat. Even though it would have been easy to call it a day, I left the ranger station to power walk my way to the finish.

MILE 100: 1 p.m. Never Give Up

I power-walk the next 15 miles chatting with other runners chasing the 2 p.m. cutoff.

Running isn’t an option. So I just focus on moving forward, one step at a time, one mile at a time.

About five hours later, the finish finally comes into view with an hour to spare.

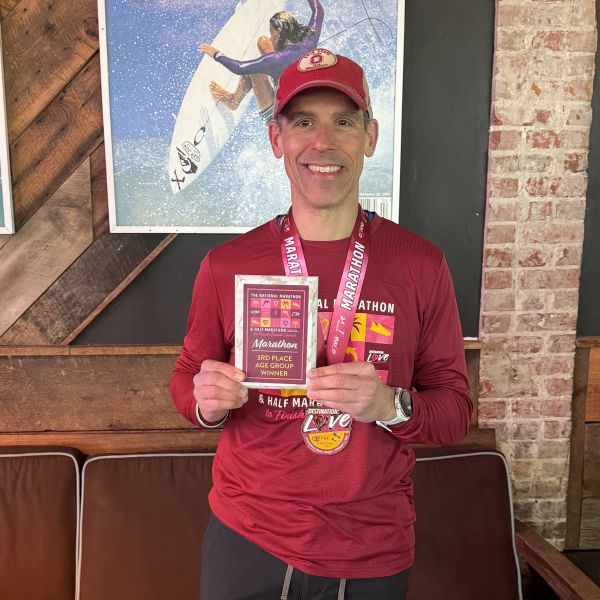

More cowbell, hugs, a few tears. And I wolf down a plate of pancakes, bacon, eggs, and hashbrowns. Then chase it down with two ice-cold glasses of chocolate milk.

1. Expect the unexpected. Every 100-mile race is hard. I’ve ran the Mountain Lakes 100 seven times. And every race is a little different. Snow, wind, rain, heat, getting lost, extreme fatigue, blistering, vomiting, crushing self-doubt. I’ve experienced it all over the years. When you set out to run 100 miles, you have to be willing to accept the fact that things might not go as planned.

2. Training pays off. I spent the last 9 months training for this race. Long runs, speed work, strength training + experimenting with nutrition and hydration. The more prepared you are, the more confidence you’ll have when you step up to the starting line.

3. Aid station support + crew is critical. Your crew and/or aid station support is critical to help you keep going. My ride-or-die saved the race for me by helping me get warm, change shoes and clothes, and keep going. Running 100 miles might feel like a solo experience at times, but most of us count on support to go the distance. Be grateful for aid station volunteers and your crew.

4. Failure is always a possibility. It’s hard to stomach when we’re so conditioned to expect success. My running friend Mikey Morales trained relentlessly for Mountain Lakes 100, but early signs of hypothermia ultimately took him out. (No doubt he’ll be back!) And he wasn’t the only runner forced to drop. If you want to run 100 miles, you have to be OK with the fact that you might not always get a buckle.

5. Running 100 miles changes you. It serves as a reminder you can do hard things. It helps you practice pushing out negative thoughts. It forces you to play the long game, training for months to go the distance. And it teaches you to keep moving towards your goals, even if the outcome is uncertain.

Thinking about running 100 miles? I’ll see you out there.

-Evan

David Moore Congratulations on #6 Evan!! What an amazing (and well supported) accomplishment! Perhaps a new method for my next race when I feel like I’m done too.

Brynn Cunningham Way to go, Evan! Huge congratulations. Oh it sounds so cold lol. Injury-free for 25 years is IMPRESSIVE. I'd love to read a story on how to do that :)

Rob Myers Nice job Evan! 100 miles is long way to go. Very impressive!

Login to your account to leave a comment.

We Want to Give it to You!